Natural building is a bit of a nebulous term; what does it even mean? Let’s start with what it isn’t. It’s not cement or steel or composite products. It’s not typically commercial buildings (though it can be), and definitely not industrial (no

factories). And, rarely is it built by machines or using high tech systems.

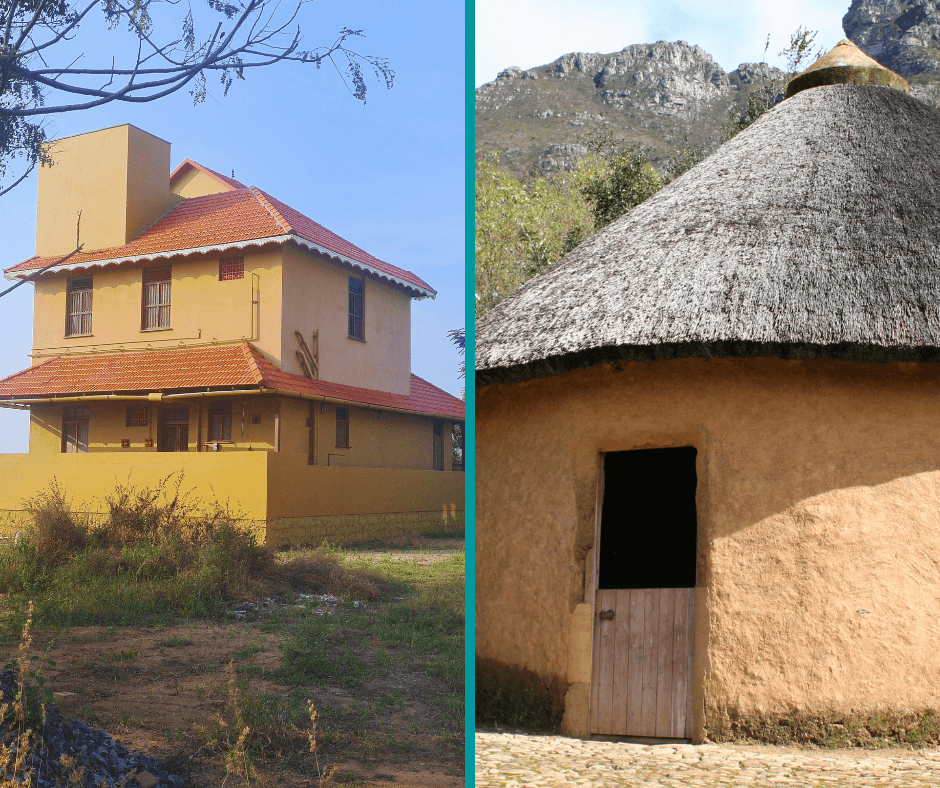

No, natural building is the use of naturally occurring building materials to construct simple structures using fairly traditional techniques, trades and crafts. The materials are usually renewable and thus sustainable (the primary plus). It tends to be labour intensive (a major downside), although often unskilled, and the materials are comparatively cheap, or even free (a definite bonus). Natural buildings are generally repairable – even without specialist trades. And they are adaptable – whether you’re talking about second storeys, home extensions, curves/round shapes or straight lines, small or large footprint, modern or rustic.

[Photo: Left is a cob 2 storey house in Tiruvannamali (India), Right is a mud hut with thatched roof in South Africa]

However, what is often misunderstood or underestimated, is how strong, durable, thermally efficient (therefore energy efficient) and comfortable they are to live and work in. Plus, natural buildings are usually wholly or mostly recyclable at their end of life. And it is these factors which I believe makes natural building a superior option for a climate adaptive world.

There are a lot of types of base materials that fall under the ‘natural building’ umbrella. Each have their own pros and cons, costs, unique challenges, techniques etc. Here’s a snapshot of the what, how and why of each, and importantly, what’s not to love:

1. Hempcrete

Racing ahead in Australia, hempcrete is an increasingly popular choice. With the gradual introduction of hemp blocks, which removes some of the labour, it looks set to be a leader in the field.

WHAT: Currently in Australia, hempcrete is not approved as a structural, load-bearing method of construction, so it is uses

hemp fibre mixed with lime, sand and water to infill timber framed walls.

HOW: Formwork is attached to the timber frame, and layer by layer the hempcrete is deposited and then hand-tamped to compress the fibre. It’s so easy even kids can do it! (See this video on a hempcrete build in Castlemaine)

WHY: It’s extremely thermally efficient, lowering the internal temperatures massively. It’s breathable and fire resistant (due to the lime). Internally it can be left natural, and by adding oxides during mixing, and laying the hempcrete in attractive, wavy layers, it is really beautiful.

[Photo: South Street hemp home extension in Melbourne, Australia]

WHY NOT: Hemp is still a fledgling industry in Australia, and often has to be purchased from faraway places and transported many miles across the sea to build a sustainable home. It also requires specialist mixers, formwork (which requires skill to attach), and the internal fixtures and fittings, electrical and plumbing all need to be planned in advance. Retrofitting into the walls is not possible. The regulations in Australia determines that a timber frame is required, which adds to the cost.

Hempcrete goes mainstream: Grand Designs Australia

2. Cob

Let’s get something straight. Many of the other types are different ways to mix and apply mud. Not dirt. Not top soil. But carefully balanced mixes of sand and clay (and inevitably silt), plus aggregates.

WHAT: Cob is mud mixed with fibres, usually straw of some description, depending what’s locally prevalent.

HOW: You mix it in a big pit (usually by foot stomping!) and then just start layering it to form it into a wall. It is load-bearing, so you don’t need additional wall supports (like columns), but it requires a footing system (see this report to learn more about footing systems), and connection to the roof using beams and rafters to distribute the load.

[Photo: Cob stomping; Thannal campus, Tiruvannamalai, India]

WHY: Ideally, most of this mud comes from the land on which you’re building. Talk about zero miles! And low cost. Building with cob is not totally unskilled, but it’s not rocket science either, so anyone can build themselves a home. It is incredibly strong (if you get your mix right), and it is one of the most adaptable materials. Want round windows? No problem. Want a bench seat or bay window in-built in the wall? Done. Whether you prefer a regular-looking, smooth finish, or you like the rustic look, you can achieve either with cob walls and your plaster finishes. Again, it is breathable, and because it’s a thermal mass, it keeps the inside very cool even when outside is blazing hot.

[Photo: Cob structure; Thannal campus, Tiruvannamalai, India - with HOT concrete box in background]

WHY NOT: It takes an enormous amount of mud! And testing of the mud to get the recipe right so it wont crack, or dust. And just like a weatherboard house needs repainting for maintenance, a cob house must receive periodic lime rendering to

protect it from the elements.

3. Wattle & Daub

A funny name for an age-old technique.

WHAT: I was struck by the similarities of wattle & daub with plaster & lath that is common in older Melbourne homes as a way to clad internal walls. However, wattle & daub is used to create a complete infill wall, not just cladding.

HOW: The ‘wattle’ part is creating a woven frame out of vines and bamboo. Mud mixed with straw is then ‘daubbed’ on to the frame to fill it. It has to be held between columns at regular intervals because it is not structural.

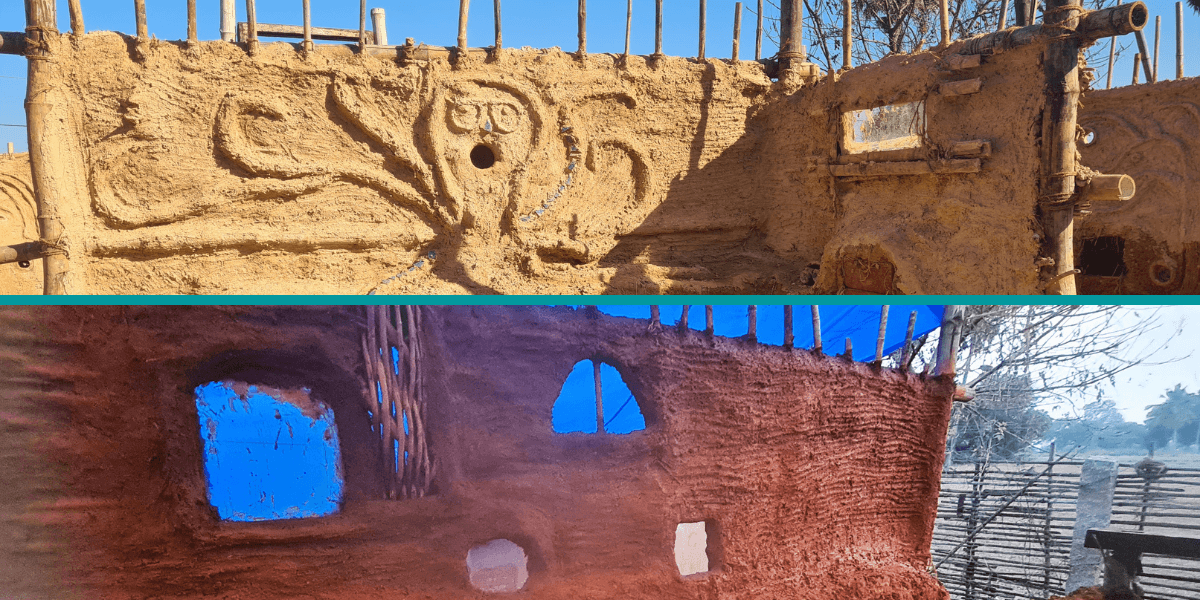

[Photos: Thannal 10 day Natural Building intensive course, Tiruvannamalai, India]

WHY: All the advantages of cob, but using less mud, and so the walls are less thick. And, if you’ve ever fancied a decorative octopus motif in your wall, you can do that with wattle & daub!

[Photos: Thannal 10 day Natural Building intensive course, Tiruvannamalai, India]

WHY NOT: It’s not structural, you may not be able to find suitable weaving material for the frames, and all parts of the wall (such as windows) must be incorporated from the very beginning into the weave. They can be hard to get right.

4. Straw Bale

I am much less familiar with strawbale, truth be told, but when I think US-style barn raising, I think straw bale.

WHAT: Literal straw bales, which are compressed and dried and formed into a wall.

HOW: Interlocking bales of straw are laid like bricks and tied into a frame (walls are not usually independently structural). It is then essential to render the walls to provide, weather, fire and pest protection.

WHY: Excellent insulative properties, and you can attach things like shelves and cabinetry easily to the walls. By using natural renders, the walls are highly breathable.

WHY NOT: Without a full, in-tact skin (render), the bales are susceptible to pests and moisture, so proper, regular maintenance is critical. Also, strawbale requires a lot of wire and steel reinforcement, so not strictly 'natural'.

5. Adobe Blocks

Think of adobe as D-I-Y brick making.

WHAT: Abode bricks are mud bricks mixed with fibre (such as straw), formed in removable moulds of variable sizes, and left to dry in the sun.

[Photo: Adobe brick making; Thannal campus, Tiruvannamalai, India]

HOW: Once the bricks are dried, a mortar mix (roughly the same recipe as the brick mixture) is used to lay them just like regular masonry. There are a few specific bricklaying patterns that provide superior wall strength.

WHY: Adobe bricks are a more regularised shape as compared with cob, so less work is required to finish them. All the advantages of a brick building without having to buy fired bricks. Adobe bricks are super strong.

[Photo: Sam testing mud brick strength after drying]

WHY NOT: You’ll need a very large space to dry the bricks, including keeping them on a tarp or something so they aren’t in contact with anything that will draw moisture too quickly. Calculating brick number and the appropriate sizes can be an overwhelming task for inexperienced builders. A masonry tradesperson may be required.

6. Compressed Stabilised Earth Bricks (CSEB)

Mud by any other name.

WHAT: CSEB are made by mechanical means – the mix is less wet than adobe bricks but are still air-dried.

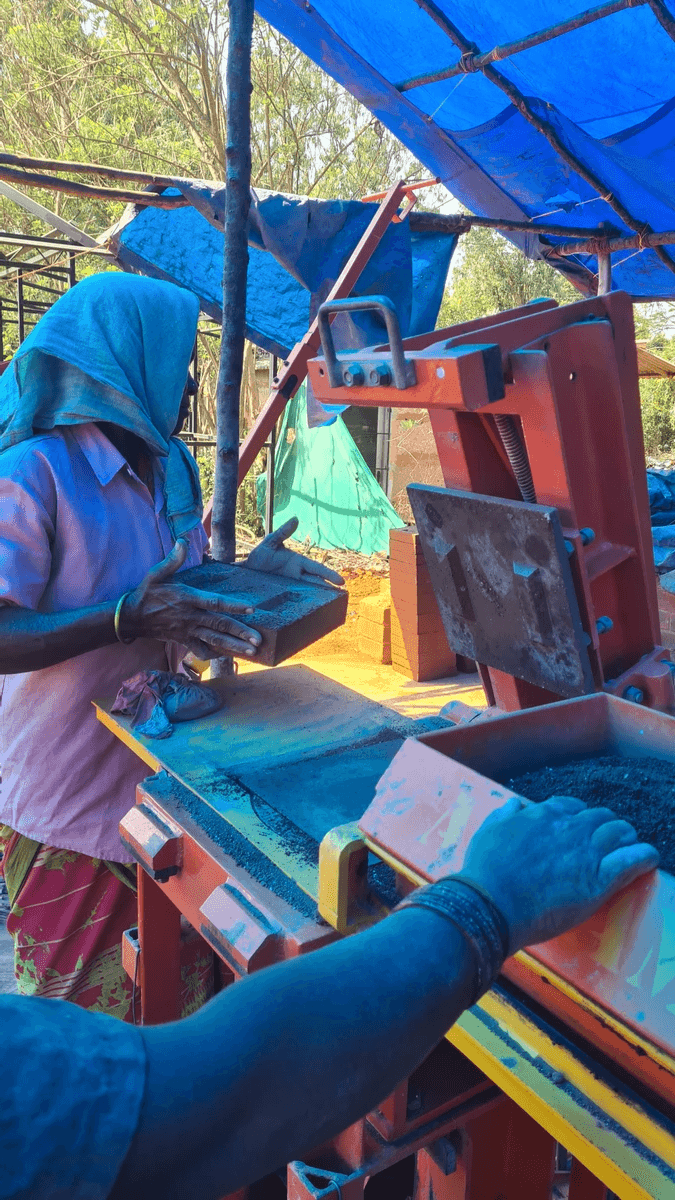

[Photo: Commercial production of CSEB; AuroYali Earth Construction, Auroville, India]

HOW: Like regular bricks and adobe bricks, they form a wall over the footings by being laid in a pattern and adhered with mortar.

WHY: Not firing bricks in a kiln is an enormous energy saving, so this is a massive win for the environment, and still produce a smooth, uniform brick. As they are made from local mud, the potential cost saving is enormous.

WHY NOT: They’re quite delicate to handle until dry. Storage is also an issue while drying. Plus, the need for the specialist equipment is a major turn-off, so unless you can buy CSEB from a supplier, it’s probably not feasible.

[Photo: AuroYali CSEB storage yard; Auroville, India]

7. Rammed Earth ('Super Adobe' and 'Hyperadobe')

The most non-conventional looking option. The technique actually came from trench building in the world wars.

[Photo Credit: Curvatecture; Mojave Center, California]

WHAT: Rammed earth uses bags, ideally made of hessian, stuffed with mud, manually compressed and ‘pinned’ in place to hold them together.

HOW: There are a few ways to do this, but it again lends from masonry techniques. Tubular bags are often used, and so the resulting building is coiled into a dome or other rounded wall. Sometimes mortar is used between the layers.

WHY: Construction is comparatively fast and simple (depending on chosen method), and if you have access to veggie sacks or rice bags, it’s a great reuse of materials. Rammed earth also has the same advantages of other mud buildings in terms of thermal comfort.

[Photos: Rammed earth using rice bags stitched with jute string, Thannal Natural Homes, India]

WHY NOT: The layout is typically a bit limited, with few openings. Non-circular shapes require butressing, and domed buildings require complex mathematics to get the engineering right. They tend to be quite small sized buildings too. The bags commonly used are polyethelene (ie: plastic-based), and some types of rammed earth construction will used barbed wire to interlock the bags, so we're losing sustainability points here.

8. Natural Stone

Ah, so actually this is something I know even less about than strawbale.

WHAT: Obviously the age-old craft of stone masonry hasn’t changed all that much. Using natural stones to build load-bearing walls on a footing system.

HOW: I truly know little, but for sure you need stones of different sizes (or tooled to fit) to fill in, or rather build out, the wall. The stones are held together with a mortar, which would be limecrete in natural building.

WHY: The Little Pig knew the big, bad wolf couldn’t blow his stone house down! Apart from strength, they have fantastic thermal mass which means less heat (but can be cold!), termite and fire resistant, and will literally last millennia if need be. This makes them cost effective over their lifetime.

WHY NOT: I mean, it’s heavy, and therefore hard yakka, but also building with stone is a fairly skillful craft so you will likely need to pay for a stonemason. Additionally, although some people may be able to acquire the stones locally, cheaply or even free, you may need to buy them, and transport costs will be high. They can attract pests (including snakes!), and not being particularly breathable, damp can be an issue. Single leaf/cavity wall construction (instead of solid stone) can mitigate some of these issues.

Note that stone walls are also often used as the plinth beam (or dwarf wall) for the footings of other types of natural buildings.

If you’ve ever considered building your own home, natural building presents an excellent alternative, especially for owner-builders. If you’ve got a great community or network of friends and family who can provide the labour, you’ll save a tonne of money and be building yourself a comfortable, sustainable home for generations to come.

Building regulations in Australia are however very slow to accommodate natural building materials and techniques, so in general you’ll need sign off for a performance solution to meet the National Construction Code. There is a growing industry of natural building practitioners, architects and designers, as well as engineers, building inspectors and even council building permit departments that are expanding their knowledge, acceptance and application of natural building.

See below for some excellent external resources to continue learning:

- Natural Building Australia: https://naturalbuildingaustralia.org/ (includes a directory of workshops)

- Your Home: https://www.yourhome.gov.au/materials

- Thannal Natural Homes: https://thannal.com/ (includes a paid online course and excellent blog)

- Hemp: https://hempbuilding.au

- Cob: https://www.thiscobhouse.com/blog/ (including free and paid courses)

- Wattle & Daub: https://www.themudhome.com/wattle-and-daub.html

- Strawbale: https://www.strawbale.com/(includes free 16 day e-course)

- Adobe: https://www.solidearth.co.nz/earthbuilding-information/building-with-adobe-brick-technique/ (including technical documents)

- CSEB: https://dev.earth-auroville.com/compressed-stabilised-earth-block/ (including video library)

- Rammed Earth: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CoTlFLG_clY (including full video library/channel)

- Natural Stone: https://www.lowimpact.org/categories/shelter/stone-building/